This is the eighth article in the Perfetto series, providing an in-depth introduction to the Vsync mechanism in Android and its representation in Perfetto. The article will analyze how the Android system performs frame rendering and composition based on Vsync signals from Perfetto’s perspective, covering core concepts such as Vsync, Vsync-app, Vsync-sf, and VsyncWorkDuration.

With the popularization of high refresh rate screens, understanding the Vsync mechanism has become increasingly important. This article uses 120Hz refresh rate as the main narrative thread to help developers understand the working principles of Vsync in modern Android devices, and how to observe and analyze Vsync-related performance issues in Perfetto.

Note: This article is based on the public evolution from Android 13 to Android 16. Code snippets are aligned to AOSP main signatures, with

...used in a few places to omit non-critical branches. Always verify against your target branch.

Table of Contents

- Series Catalog

- What is Vsync

- Basic Working Principles of Vsync in Android

- Observing Vsync in Perfetto

- How Android App Frames Work Based on Vsync

- References

- About Me && Blog

Series Catalog

- Android Perfetto Series Catalog

- Android Perfetto Series 1: Introduction to Perfetto

- Android Perfetto Series 2: Capturing Perfetto Traces

- Android Perfetto Series 3: Familiarizing with Perfetto View

- Android Perfetto Series 4: Opening Large Traces via Command Line

- Android Perfetto Series 5: Android App Rendering Flow Based on Choreographer

- Android Perfetto Series 6: Why 120Hz? Advantages and Challenges of High Refresh Rates

- Android Perfetto Series 7: MainThread and RenderThread Deep Dive

- Android Perfetto Series 8: Understanding Vsync Mechanism and Performance Analysis

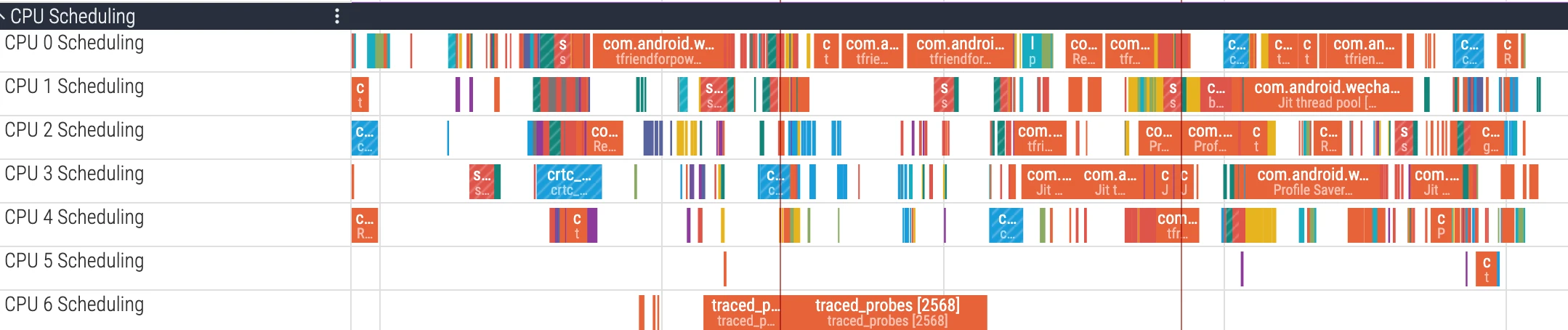

- Android Perfetto Series 9: CPU Information Interpretation

- Android Perfetto Series 10: Binder Scheduling and Lock Contention

- Video (Bilibili) - Android Perfetto Basics and Case Sharing

- Video (Bilibili) - Android Perfetto: Trace Graph Types - AOSP, WebView, Flutter + OEM System Optimization

If you haven’t read the Systrace series yet, here are the links:

- Systrace Series Catalog: A systematic introduction to Systrace, Perfetto’s predecessor, and learning about Android performance optimization and Android system operation basics through Systrace.

- Personal Blog: My personal blog, mainly Android-related content, with some life and work-related content as well.

Welcome to join the WeChat group or community on the About Me page to discuss your questions, what you’d most like to see about Perfetto, and all Android development-related topics with fellow group members.

What is Vsync

Vsync (Vertical Synchronization) is the core mechanism of the Android graphics system. Its existence is to solve a fundamental problem: how to keep the software rendering rhythm synchronized with the hardware display rhythm.

Before the Vsync mechanism existed, the common problem was Screen Tearing. When the display reads the framebuffer while the GPU writes the next frame, the same refresh will show inconsistent top and bottom parts of the image.

What Problems Does Vsync Solve?

The core idea of the Vsync mechanism is very simple: make all rendering work proceed according to the display’s refresh beat. Specifically:

- Synchronization Signal: The display emits a Vsync signal every time it starts a new refresh cycle.

- Frame Beat and Production: On the application side, when Vsync arrives, Choreographer drives the production of a frame (Input/Animation/Traversal); after the CPU submits rendering commands, the GPU executes asynchronously in a pipeline. On the SurfaceFlinger side, when Vsync arrives, Buffer composition operations are performed.

- Buffering Mechanism: Using double buffering or triple buffering technology ensures the display always reads complete frame data.

This way, frame production and display are aligned with Vsync as the beat. Taking 120Hz as an example, there’s a display opportunity every 8.333ms; the application needs to submit a compositable Buffer to SurfaceFlinger before this window. The key constraint is the timing of queueBuffer/acquire_fence/present_fence; if it doesn’t catch up with this cycle, it will be delayed to the next cycle for display.

Basic Working Principles of Vsync in Android

Android system’s Vsync implementation is much more complex than the basic concept, needing to consider multiple different rendering components and their coordinated work.

Layered Architecture of Vsync Signals

In the Android system, there isn’t just one simple Vsync signal. In fact, the system maintains multiple Vsync signals for different purposes:

Hardware Vsync (HW Vsync):

This is the lowest-level Vsync signal, generated by the display hardware (HWC, Hardware Composer). Its frequency strictly corresponds to the display’s refresh rate, for example, a 60Hz display generates HW Vsync every 16.67ms, and a 120Hz display generates one every 8.333ms. (Hardware Vsync callbacks are managed by HWC/SurfaceFlinger, see frameworks/native/services/surfaceflinger related implementation)

However, HW Vsync is not always on. Since frequent hardware interrupts consume considerable power, the Android system adopts an intelligent strategy: only enabling HW Vsync when precise synchronization is needed, and using software prediction to generate Vsync signals most of the time.

Vsync-app (Application Vsync):

This is a Vsync signal specifically used to drive application layer rendering. When an application needs to perform UI updates (such as user touch, animation running, interface scrolling, etc.), the application will request to receive Vsync-app signals from the system.

1 | // frameworks/base/core/java/android/view/Choreographer.java |

Vsync-app is requested on-demand. If the application interface is static with no animations or user interaction, the application won’t request Vsync-app signals, and the system won’t generate Vsync events for this application.

Vsync-sf (SurfaceFlinger Vsync):

This is a Vsync signal specifically used to drive SurfaceFlinger for layer composition. SurfaceFlinger is the service in the Android system responsible for compositing all application layers into the final image.

Vsync-appSf (Application-SurfaceFlinger Vsync):

A new signal type introduced in Android 13. To eliminate the timing ambiguity brought by the old design where the sf EventThread both woke up SurfaceFlinger and served some Choreographer clients, the system separated the two responsibilities: vsync-sf focuses on waking up SurfaceFlinger, while vsync-appSf faces clients that need to synchronize with SurfaceFlinger.

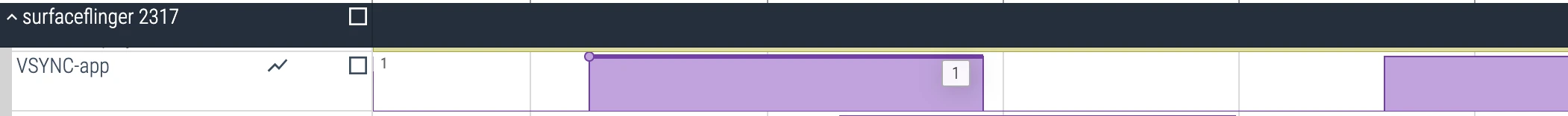

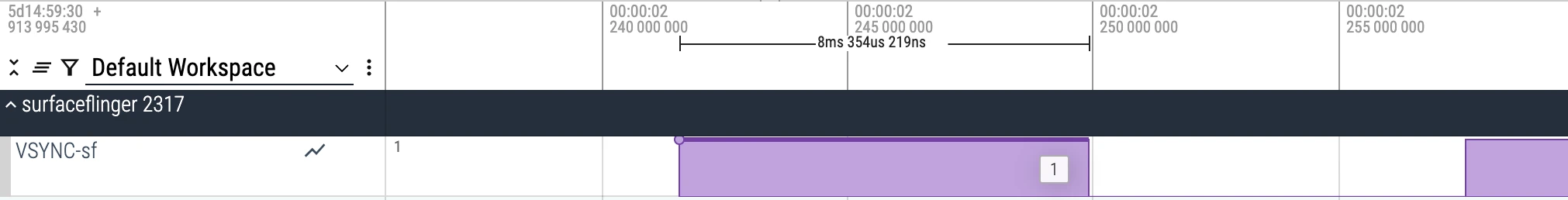

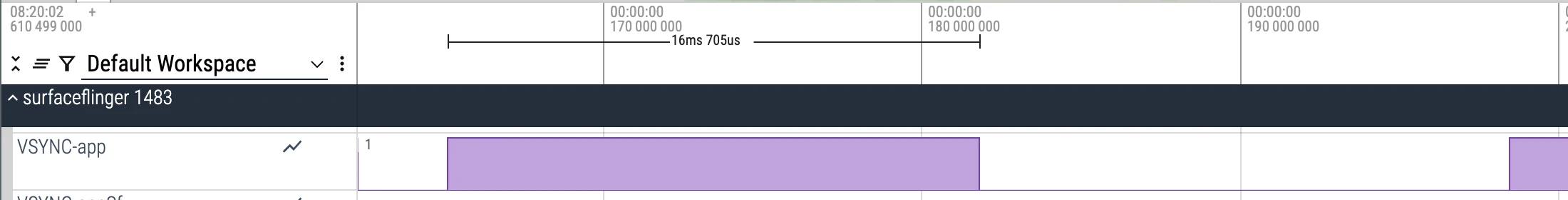

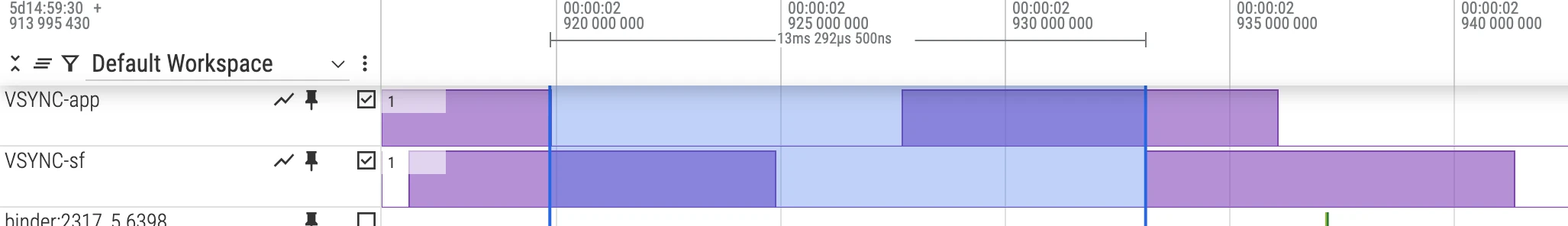

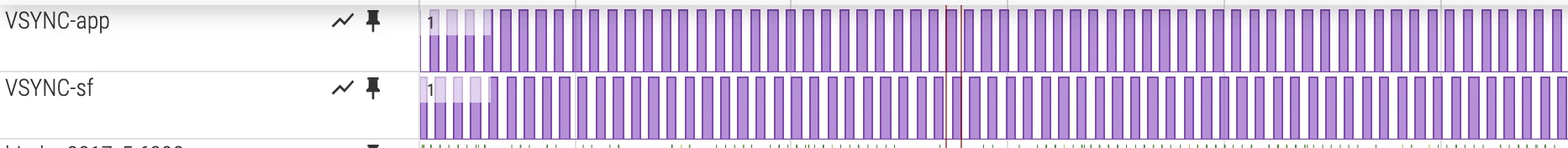

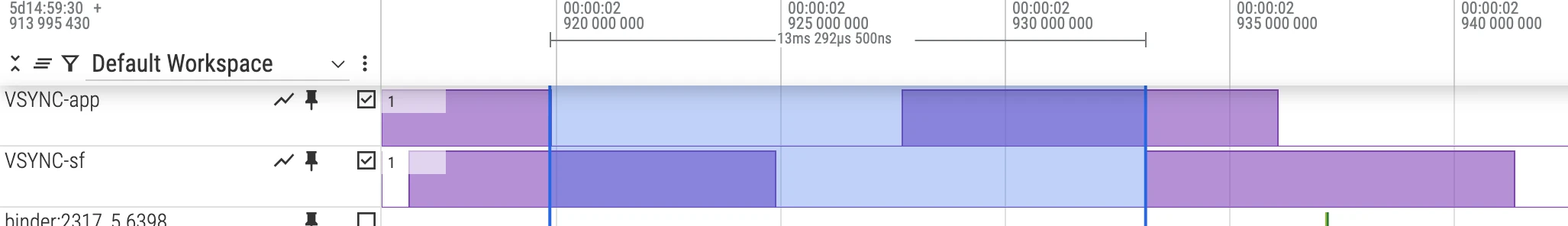

Observing Vsync in Perfetto

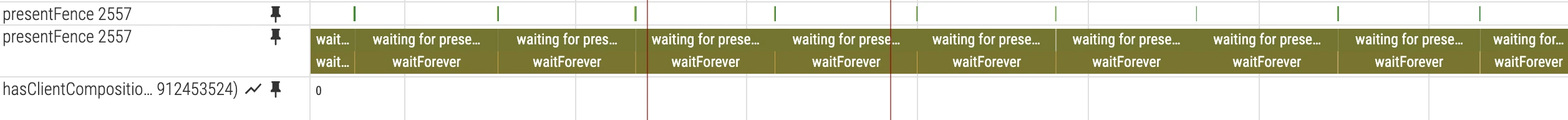

Perfetto traces contain multiple Vsync-related Tracks. Understanding the meaning of these Tracks helps analyze performance issues.

In the SurfaceFlinger Process:

vsync-app

Displays application Vsync signal status, with values changing between 0 and 1. Each value change represents a Vsync signal.

vsync-sf

Displays SurfaceFlinger Vsync signal status. When there’s no Vsync Offset, it changes synchronously withvsync-app.

vsync-appSf

Added in Android 13+, serves special Choreographer clients that need to synchronize with SurfaceFlinger.

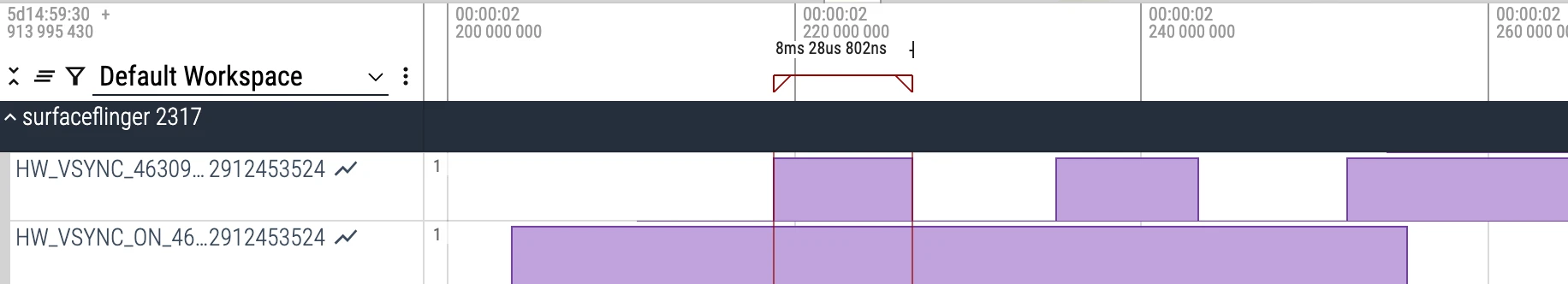

HW_VSYNC

Displays hardware Vsync enabled status. Value of 1 means enabled, value of 0 means disabled. To save power, hardware Vsync is only enabled when precise synchronization is needed.

In the Application Process:

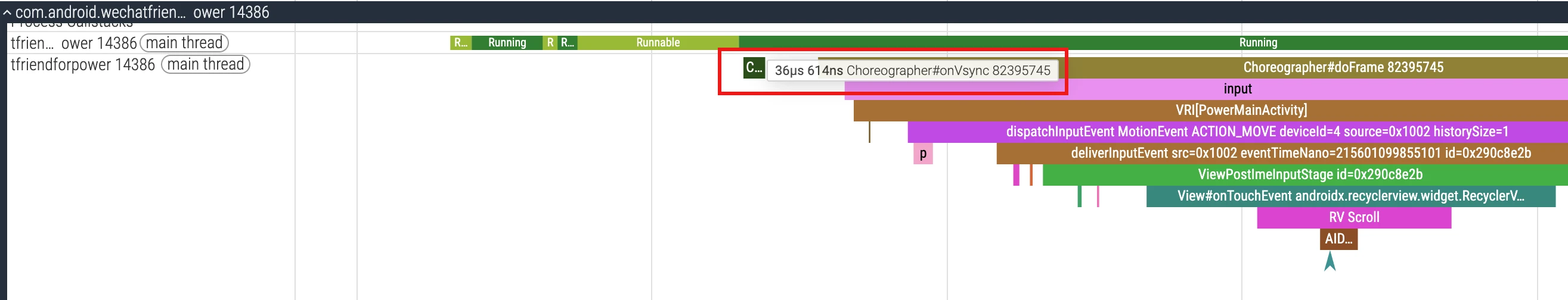

FrameDisplayEventReceiver.onVsync Slice Track:

Displays the time point when the application receives Vsync signals. The connection is established through Binder, while events are delivered through BitTube/Looper channels, so timing may be slightly later than vsync-app in SurfaceFlinger.

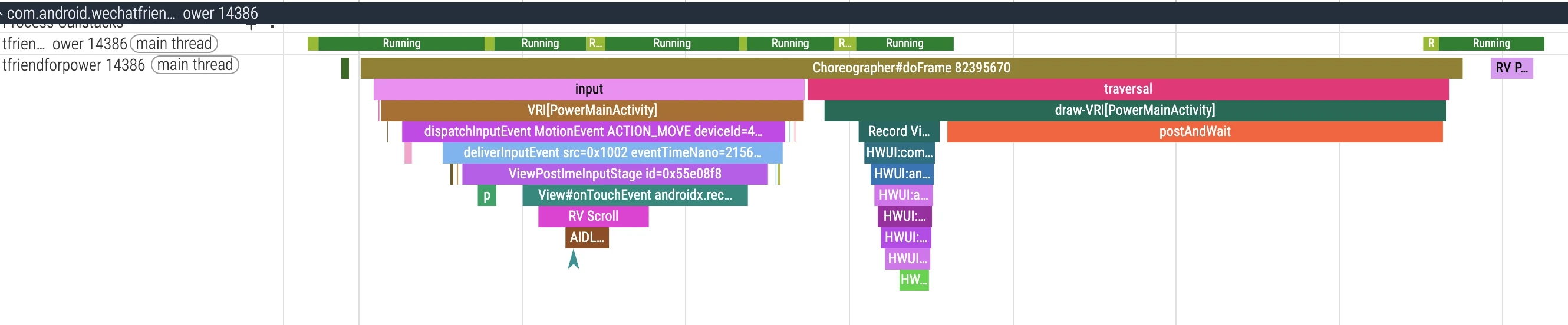

UI Thread Slice Track:

Contains Choreographer#doFrame and related Input, Animation, Traversal, etc. Slices. Each doFrame corresponds to one frame’s processing work.

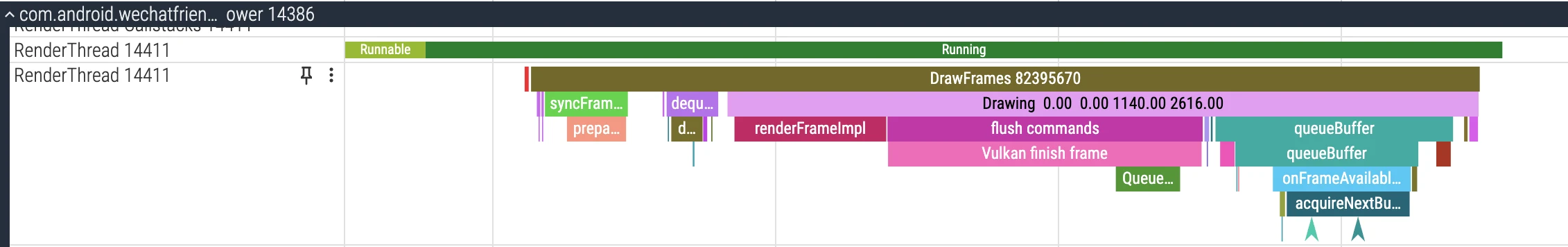

RenderThread Slice Track:

Contains DrawFrame, syncAndDrawFrame, queueBuffer, etc. Slices, corresponding to render thread work.

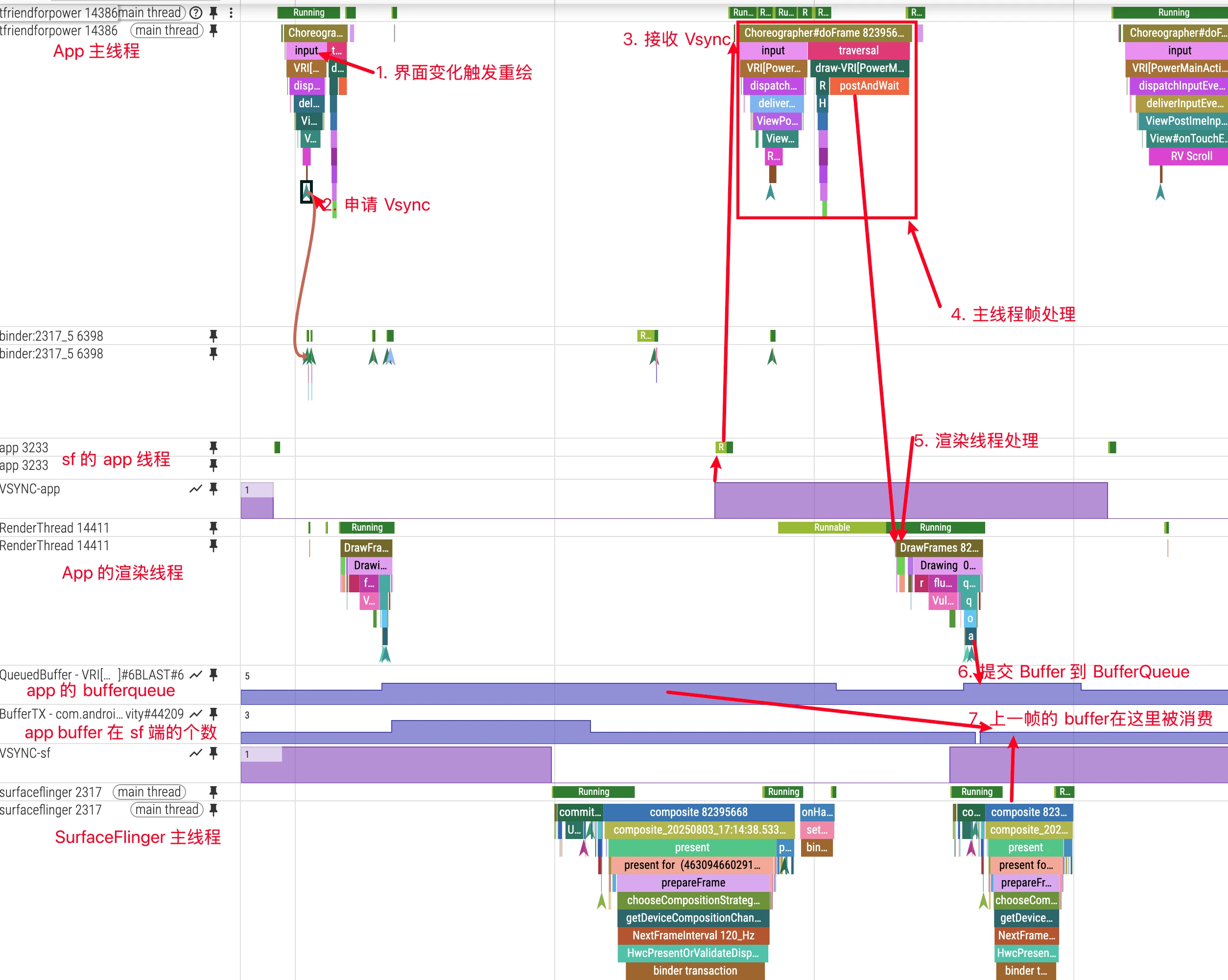

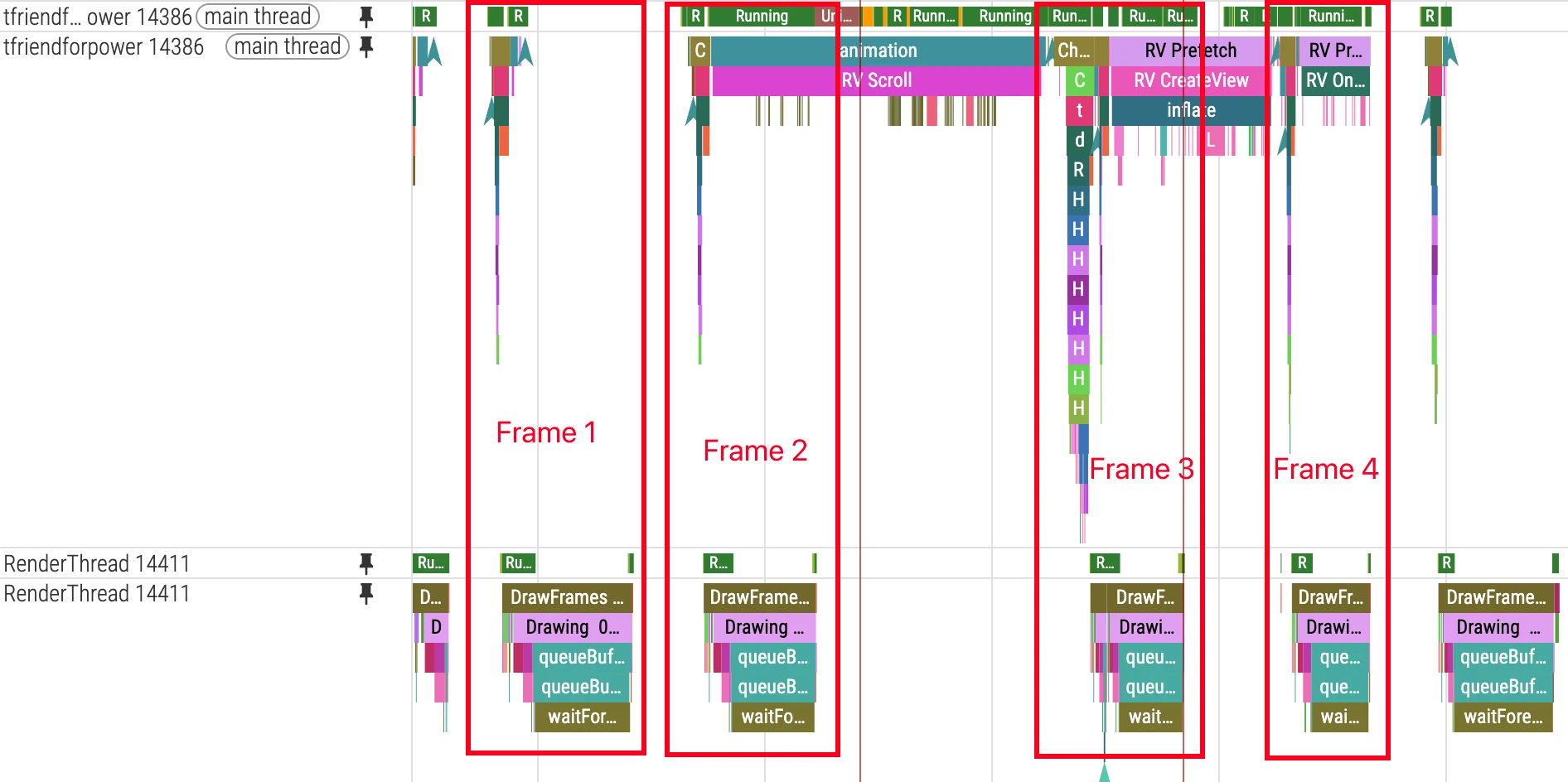

How Android App Frames Work Based on Vsync

Each frame of an Android application completes the entire process from rendering to display based on the Vsync mechanism, involving multiple key steps.

Process Overview (In Order)

- Trigger Redraw/Input:

View.invalidate(), animation, data change, or input event triggers →ViewRootImpl.scheduleTraversals()→Choreographer.postCallback(TRAVERSAL) - Request Vsync:

Choreographerrequests next Vsync (app phase) throughDisplayEventReceiver.scheduleVsync() - Receive Vsync: After

DisplayEventReceiver.onVsync()receives Vsync, it posts an asynchronous message to the main thread message queue - Main Thread Frame Processing:

Choreographer.doFrame()executes five types of callbacks in order:INPUT → ANIMATION → INSETS_ANIMATION → TRAVERSAL → COMMIT - Rendering Submission:

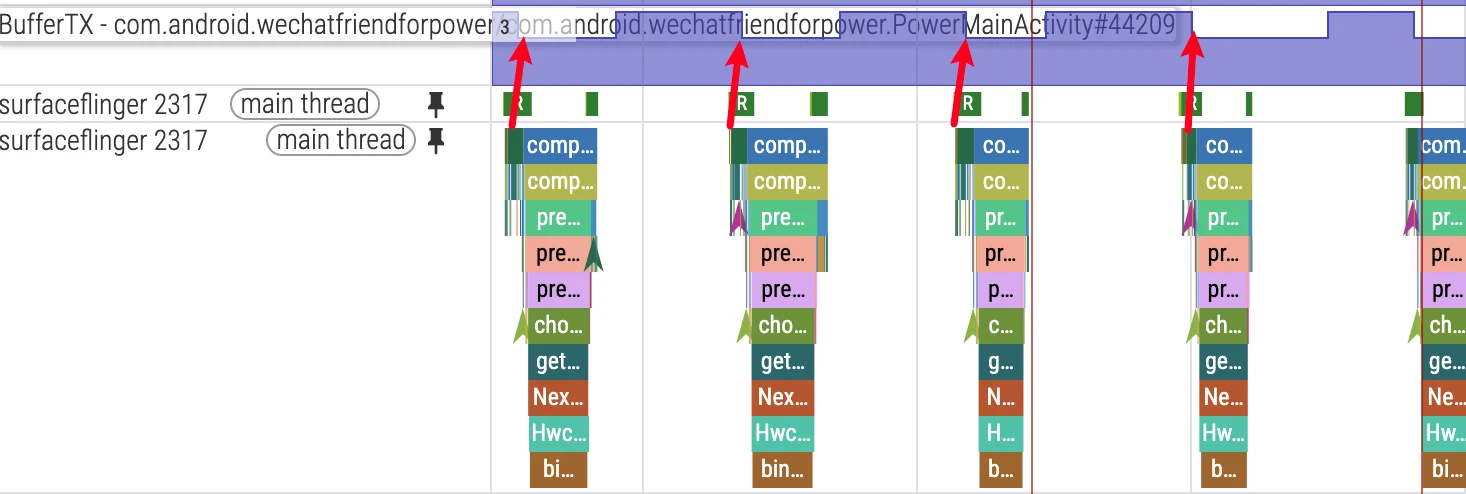

RenderThreadexecutessyncAndDrawFrame/DrawFrame, CPU records GPU commands,queueBuffersubmits to BufferQueue - Composition Display:

SurfaceFlingercomposites (GPU/or HWC) whenvsync-sfarrives, generatespresent_fence, outputs to display - Frame Completion Measurement: Determines whether displayed on schedule through

FrameTimeline(PresentType/JankType) andacquire/present_fence

Below we’ll expand on each step’s key implementation and Perfetto observation points.

When Does App Request Vsync Signals

Applications don’t request Vsync signals all the time. Vsync signals are requested on-demand, only in the following situations will applications request the next Vsync from the system:

Scenarios Triggering Vsync Request:

- UI Update Needs: When View calls

invalidate() - Animation Execution: When ValueAnimator, ObjectAnimator, and other animations start

- User Interaction: Touch events, key events, etc. requiring UI response

- Data Changes: RecyclerView data updates, TextView text changes, etc.

Complete Process of App Requesting Vsync

When an application needs to update UI, it requests Vsync signals through the following process:

1 | // 1. UI component requests redraw |

TRAVERSALis still the most common trigger, but in AOSP main it is not the only path that requests Vsync.

How Main Thread Listens for Vsync Signals

The application main thread listens for Vsync signals through DisplayEventReceiver. This process involves several key steps:

1. Establish Connection:

1 | // frameworks/base/core/java/android/view/Choreographer.java |

2. Receive Vsync Signal:

1 |

|

Several Remaining Questions

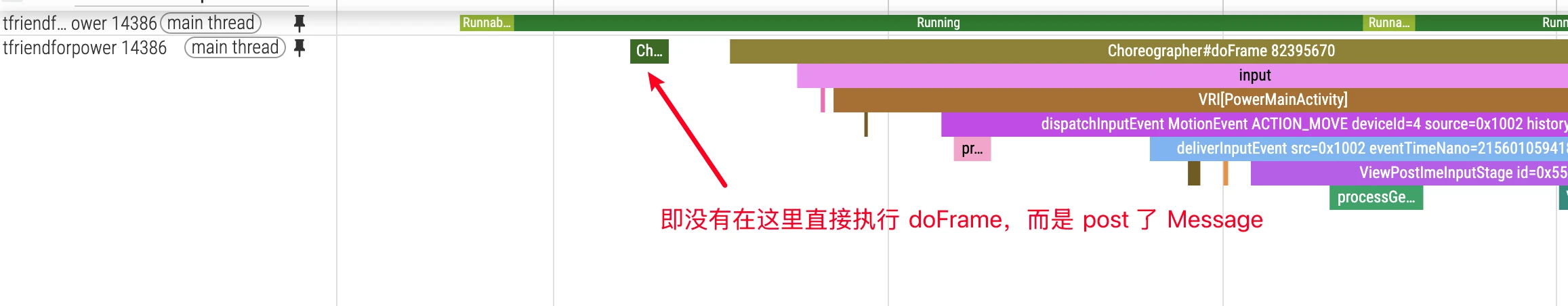

Q1: Why not execute doFrame() directly in onVsync()?

- Thread boundary: In the

Choreographerpath,onVsync()runs on the bound Looper (usually the main thread). Routing work through the message queue beforedoFrame()keeps frame scheduling unified and ordered. - Scheduling control: Precisely align execution moment through

sendMessageAtTime() - Queue semantics: Enter main thread MessageQueue, ensure coordination with other high-priority tasks

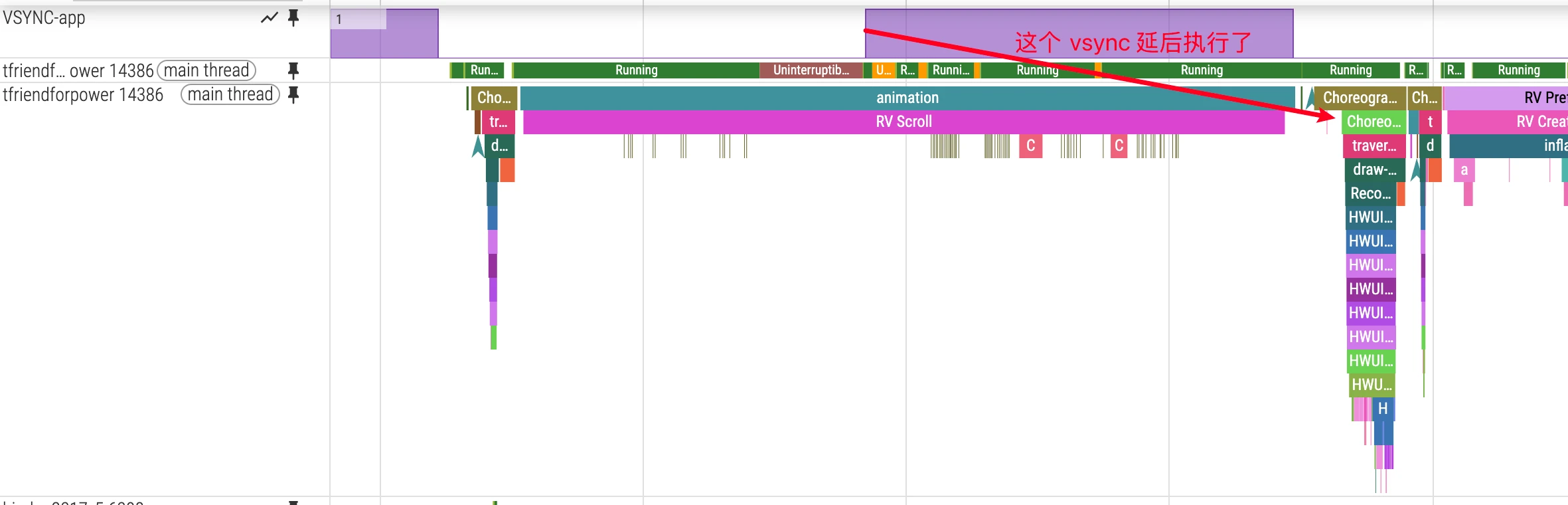

Q2: If Vsync message arrives but main thread is busy, will it be lost?

- Not strictly “no loss”. A single

scheduleVsync()is a one-shot request. If the main thread stays busy, multiple hardware beats may be skipped and only a newer frame gets processed. Use FrameTimeline to decide whether this became visible jank. - AOSP

DisplayEventDispatcher::processPendingEventsexplicitly overwrites older vsync events with newer ones (only the most recent one is dispatched).

Q3: Must CPU/GPU complete within a single Vsync cycle? If any link exceeds 1 vsync, will it cause frame drops?

Modern Android systems use multi-buffering (usually triple buffering) mechanism:

Application side: Front Buffer (displaying) + Back Buffer (rendering) + possible third Buffer

SurfaceFlinger side: Also has similar buffering mechanism

This means even if one application frame exceeds the Vsync cycle, it won’t necessarily drop frames immediately.

GPU asynchronous pipeline; the key is whether

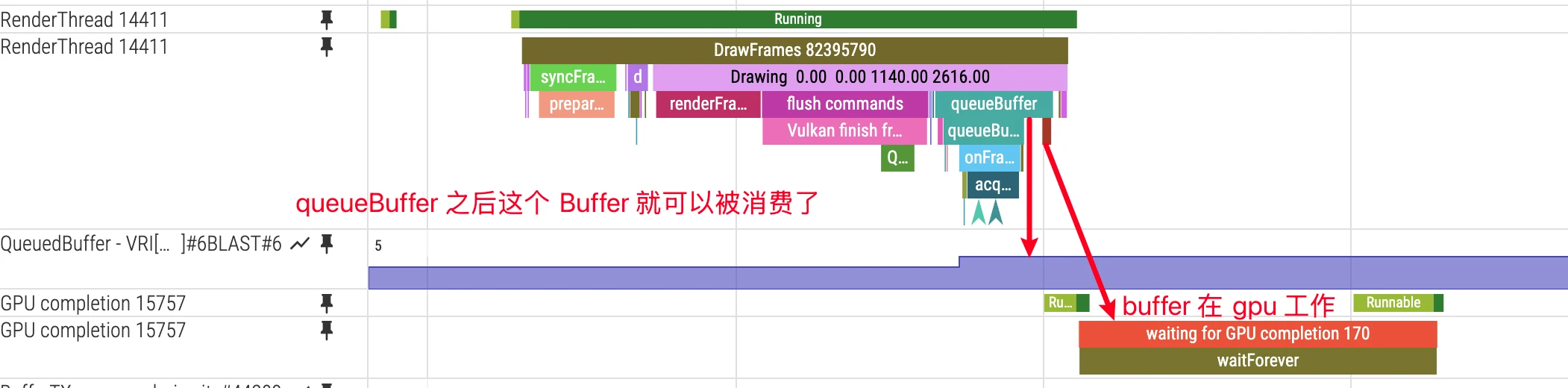

queueBuffercatches up with SF composition window. Multi-buffering can mask single frame delays but may introduce additional latency. As shown in the figure below, both App-side BufferQueue and SurfaceFlinger-side Buffers are sufficient with redundancy, so no frames are dropped.However, if the App hasn’t accumulated Buffers before, frame drops will still occur.

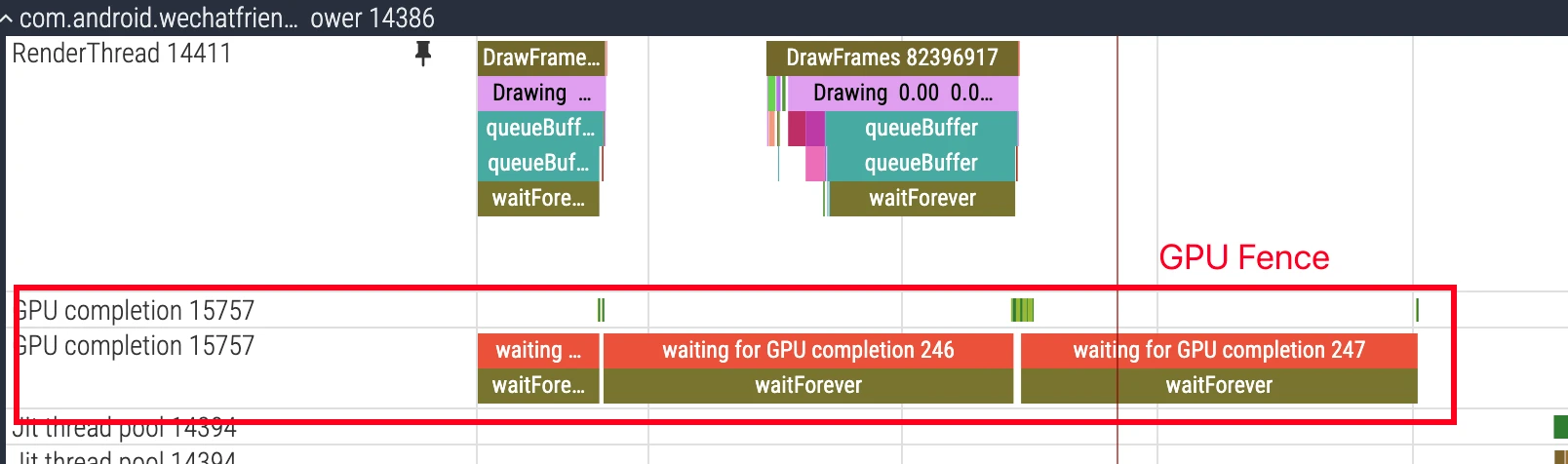

Q5: How do GPU and CPU coordinate?:

GPU rendering is asynchronous, bringing additional complexity:

- CPU works normally, GPU becomes bottleneck: Even if application main thread completes work within Vsync cycle, excessive GPU rendering time will still cause frame drops

- GPU Fence mechanism: In the latch stage, the critical sync point is usually

acquire fence(when the Buffer is safe to read).present fenceis more about when the frame is actually presented on display. With the systemLatch Unsignaled Buffersstrategy, SurfaceFlinger can move forward first under certain conditions, then wait on fence only when needed, hiding part of the latency.

Q6: What is the real role of Vsync Phase (phase difference)?:

- Improve touch responsiveness: By adjusting sf vsync’s phase difference, the time from when an application starts drawing to displaying on screen can be shortened from 3 Vsync cycles to 2 Vsync cycles. This is very important for interaction scenarios like touch response.

- Solve application drawing timeout issues: When application drawing times out, a reasonable sf phase difference can buy more processing time for the application, avoiding frame drops due to improper timing.

VsyncWorkDurationis closer to scheduling budget visualization (workDuration/readyDuration) and is not a 1:1 mapping to a single app offset value. Correlate it withvsync-app/sfand FrameTimeline.- The time period shown in the figure below is the app offset (13.3ms) configured on my phone

Technical Implementation of Vsync Offset / WorkDuration

In current AOSP main, the entry point is the VsyncConfiguration abstraction, which returns a VsyncConfigSet organized by scenario. Implementation-wise, PhaseOffsets is the legacy path, while WorkDuration is one of the common paths in newer systems:

1 | // frameworks/native/services/surfaceflinger/Scheduler/VsyncConfiguration.h |

Key Concepts:

workDuration/readyDuration: scheduling budget and lead time used to compute callback wakeupapp/sf offset: still useful as an analysis lens, but it is an outcome of config sets plus scheduler model- In common practice, “app/sf offset delta” means their phase gap (often viewed as

|sfOffset - appOffset|; sign conventions depend on device implementation and metric definition)

Actual Optimization Effects

Taking a 120Hz device as an example, the effect of configuring 3ms Offset:

Without Offset (Traditional Method):

- T0: Application and SurfaceFlinger receive Vsync simultaneously

- T0+3ms: Application completes rendering

- T0+8.333ms: Next Vsync, SurfaceFlinger starts composition

- T0+16.666ms: User sees the image (total latency 16.666ms)

With Offset (Optimized Method):

- T0+1ms: Application receives Vsync-app, starts rendering

- T0+3ms: Application completes rendering, submits Buffer

- T0+4ms: SurfaceFlinger receives Vsync-sf, immediately starts composition

- T0+6ms: SurfaceFlinger completes composition

- T0+8.333ms: User sees the image (total latency 8.333ms)

Through reasonable Offset configuration, latency can be reduced from 16.666ms to 8.333ms, doubling response performance.

Actual Time Budget Allocation:

Taking a 120Hz device as an example (8.333ms cycle):

- Ideal case: Application 4ms + SurfaceFlinger 2ms + buffer 2.333ms

- But actually acceptable: Application 6ms + SurfaceFlinger 3ms (if there’s enough Buffer buffering)

- GPU limitation: On low-end devices, GPU rendering may need 10-15ms, becoming the real bottleneck

Real Causes of Frame Drops:

- Application timeout + Buffer exhaustion: Continuous multiple frame timeouts lead to no available Buffers in BufferQueue

- GPU rendering timeout: Even if CPU work is normal, GPU rendering timeout will still cause frame drops

- SurfaceFlinger timeout: System-level composition timeout affects all applications

- System resource competition: CPU/GPU/memory and other resources occupied by other processes

Complete Code Flow of Vsync Signals

The complete chain of Vsync signals from hardware to application layer is as follows.

Key Code Paths Aligned with AOSP main (Condensed Excerpts)

The snippets below are aligned with current AOSP main method signatures, with non-essential branches/logging omitted.

1) Choreographer requests the next Vsync (Java)

1 | // frameworks/base/core/java/android/view/Choreographer.java |

2) Choreographer receives Vsync (Java)

1 | // frameworks/base/core/java/android/view/Choreographer.java |

3) JNI bridge: DisplayEventDispatcher (C++)

1 | // frameworks/base/core/jni/android_view_DisplayEventReceiver.cpp |

4) Native transport: DisplayEventReceiver + BitTube (C++)

1 | // frameworks/native/libs/gui/DisplayEventReceiver.cpp |

5) SurfaceFlinger scheduling and distribution (C++)

1 | // frameworks/native/services/surfaceflinger/Scheduler/VSyncDispatch.h |

1 | // frameworks/native/services/surfaceflinger/Scheduler/EventThread.cpp |

Key Timing Point Analysis

Through the above code flow, we can see the complete timing chain:

- HWC emits hardware Vsync → SurfaceFlinger Scheduler captures display cadence

- Scheduler computes wakeup window →

VSyncDispatch::schedule(...) - EventThread creates/distributes events →

DisplayEventReceiver::EventviaBitTube - App-side Native receives event →

DisplayEventDispatcher::dispatchVsync(...) - Java

FrameDisplayEventReceivercallback → async message enters Looper queue Choreographer#doFrame(...)executes → Input/Animation/Traversal/Commit

Each link has different responsibilities and optimization points. Understanding the complete process helps analyze Vsync-related performance issues in Perfetto.

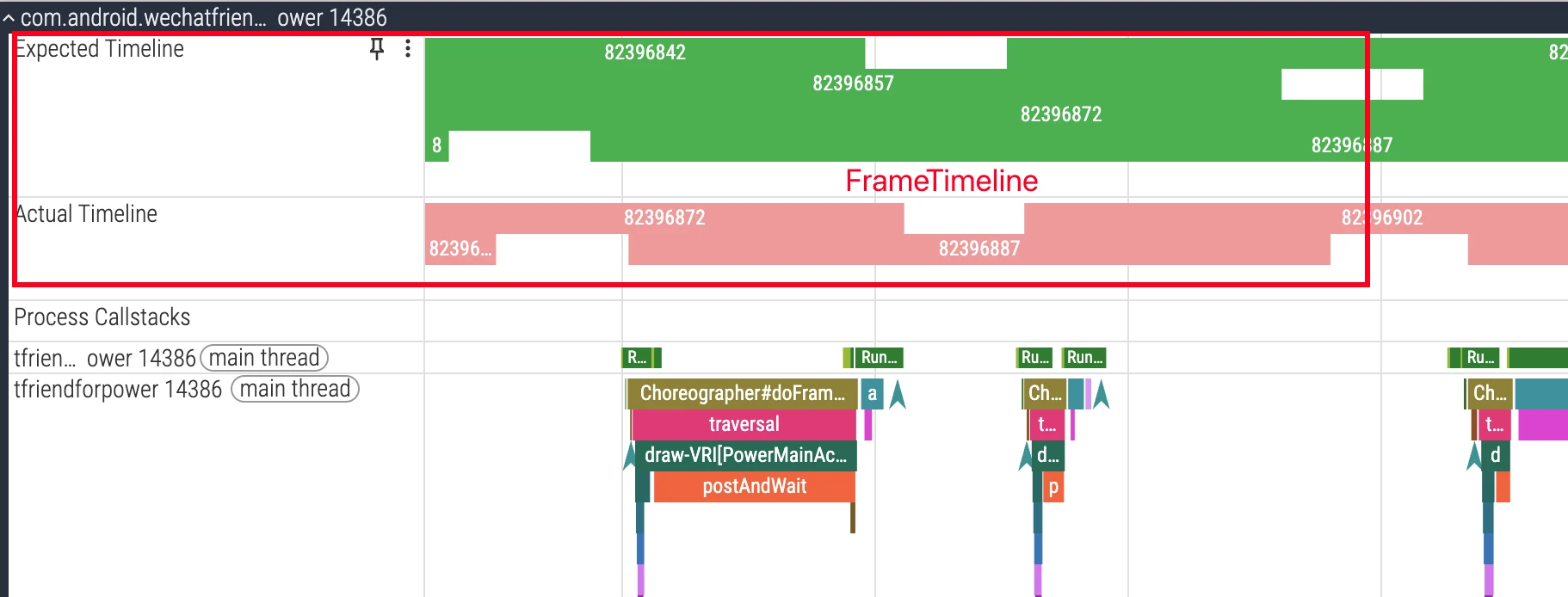

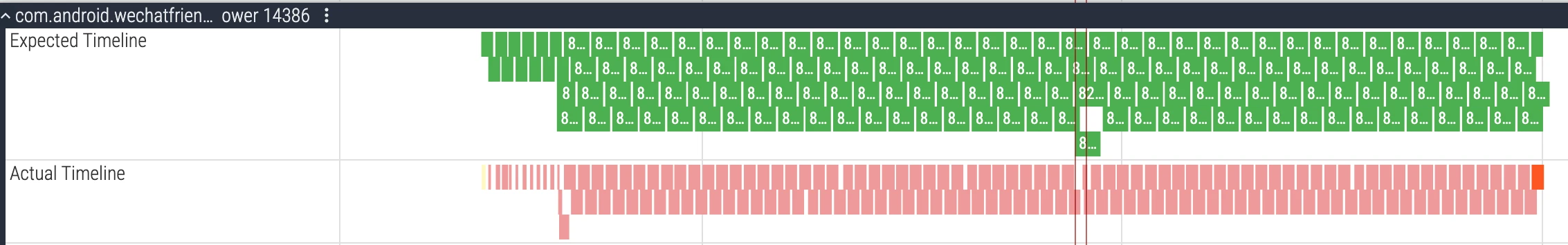

FrameTimeline

Both App and SurfaceFlinger have FrameTimeline

- Tracks:

Expected Timeline,Actual Timeline - PresentType/JankType:

- PresentType indicates how this frame was presented (e.g., On-time, Late), JankType indicates jank type source

- Common JankType:

AppDeadlineMissed,BufferStuffing,SfCpuDeadlineMissed,SfGpuDeadlineMissed, etc.

- Operation Steps (Perfetto UI):

- Select target

Surface/Layerin application process or filter using FrameToken - Align Expected with Actual, view offset and color coding

- Drill up:

Choreographer#doFrame,RenderThread,queueBuffer,acquire/present_fence

- Select target

- Avoiding Misjudgment:

- Judging frame drops solely by

doFrameduration is unreliable; use FrameTimeline’s PresentType/JankType as standard - Multi-buffering may mask single frame timeout, need to look at consecutive frames and Buffer availability

- Judging frame drops solely by

Impact of Refresh Rate/Display Mode/VRR on Vsync and Offset/Prediction

- Mode Switching: Refresh rate changes will reconfigure

VsyncConfiguration, affecting app/sf Offset and prediction model;- Perfetto: Check

display mode changeevents and subsequentvsyncinterval changes

- Perfetto: Check

- VRR (Variable Refresh Rate): Target cycle is not constant, software prediction relies more on present_fence feedback calibration;

- Perfetto: Observe

vsyncinterval distribution andpresent_fencedeviation

- Perfetto: Observe

- Multi-display/External Display: Hardware can report vsync per

physicalDisplayId; however, app-side Choreographer usually still follows internal/pacesetter timing (details vary by branch and version). Confirm whether you’re reading HWC/SF tracks or app tracks before drawing conclusions;- Version difference: official docs state per-display VSYNC was not supported on Android 10 and below; this limitation is removed at the framework/HWC capability level on Android 11+, but app-side

Choreographerrequest paths still need branch-specific verification (AOSP main still has internal-display related notes) - Perfetto: Filter related Counter/Slice by display ID

- Version difference: official docs state per-display VSYNC was not supported on Android 10 and below; this limitation is removed at the framework/HWC capability level on Android 11+, but app-side

Perfetto Practice Checklist (Recommended Viewing Order)

- Vsync Signal and Cycle

- Whether

vsync-app / vsync-sf / vsync-appSfintervals are stable (60/90/120Hz corresponding cycles) - Whether there are abnormally dense/sparse Vsyncs (prediction jitter)

- Whether

- Vsync Phase Difference Configuration

- Whether

VsyncWorkDurationmatches device’s expected app/sf Offset - Whether app and sf sequence matches “draw first then composite” strategy

- Whether

- FrameTimeline Interpretation

- First look at

PresentType, thenJankType; confirm whether it’s app or SF/GPU side issue - Select target Surface/FrameToken to locate specific frame

- First look at

- Application Main Thread and Render Thread

Choreographer#doFrameeach stage duration (Input/Animation/Traversal)- Whether

RenderThread‘ssyncAndDrawFrame/DrawFrameduration is abnormal

- BufferQueue and Fence

- Producer: After RenderThread

queueBuffer, the Buffer enters the consumable queue. Whether SF can latch it immediately still depends onacquire fence.present fenceis mainly for confirming when the frame is actually presented. Newer versions may advance with unsignaled buffers under specific policy, then wait later when needed.

- Consumer SF and BufferTX: At each composition beat, SF tries to fetch the latest available Buffer for a target layer. If BufferTX for a layer is 0, that layer usually has no new Buffer, so SF keeps composing with old content. For that app, this appears as visual stall/jank, but SF does not globally “stop composing.”

- Producer: After RenderThread

- Composition Strategy and Display

- Whether SF frequently goes ClientComposition; whether HWC validate/present is abnormal

- Whether there’s obvious prediction deviation during multi-display/mode switching/VRR

- Resources and Other Interference

- CPU competition (big core occupation), GPU busy, IO/memory jitter (GC/compaction)

- Whether other foreground apps/system services occupy key resources

References

- Android Graphics Architecture

- VSYNC Implementation Guide

- Frame Pacing

- Perfetto Documentation

- Android Perfetto Series 5: Android App Rendering Flow Based on Choreographer

- Android Perfetto Series 6: Why 120Hz? Advantages and Challenges of High Refresh Rates

- Vsync offset Related Technical Analysis

- Android 13/14 High Version SurfaceFlinger VSYNC-app/VSYNC-appSf/VSYNC-sf Analysis

- AOSP - Choreographer.java (main)

- AOSP - android_view_DisplayEventReceiver.cpp (main)

- AOSP - DisplayEventDispatcher.h (main)

- AOSP - DisplayEventReceiver.cpp (main)

- AOSP - VSyncDispatch.h (main)

- AOSP - EventThread.cpp (main)

- Android Multi-display (official)

- AOSP - VsyncConfiguration.h (main)

- AOSP - DisplayEventDispatcher.cpp (main)

- Unsignaled buffer latch (official)

About Me && Blog

Below is a personal introduction and related links. I look forward to communicating with you all. When three people walk together, one of them can be my teacher!

- Blogger Personal Introduction: Contains personal WeChat and WeChat group links.

- Blog Content Navigation: A navigation of personal blog content.

- Excellent Blog Articles Collected and Organized by Individuals - Must-Know for Android Performance Optimization: Welcome everyone to recommend yourself and recommend (WeChat private chat is fine)

- Android Performance Optimization Knowledge Planet: Welcome to join, thanks for support~

One person can go faster, a group of people can go further