This is the fifth article in the Systrace series, primarily providing a brief introduction to the workflow of SurfaceFlinger. It covers several important threads within SurfaceFlinger, including Vsync signal interpretation, app buffer display, and jank detection. Since Vsync has already been covered in Systrace Basics - Vsync Explained and Detailed Explanation of Android Rendering Mechanism Based on Choreographer, it won’t be discussed in detail here.

The purpose of this series is to view the overall operation of the Android system from a different perspective using Systrace, while also providing an alternative angle for learning the Framework. Perhaps you’ve read many articles about the Framework but can never remember the code, or you’re unclear about the execution flow. Maybe from Systrace’s graphical perspective, you can gain a deeper understanding.

Table of Contents

- Series Article Index

- Main Content

- App Section

- BufferQueue Section

- SurfaceFlinger Section

- HWComposer Section

- References

- About Me && Blog

Series Article Index

- Introduction to Systrace

- Systrace Basics - Prerequisites for Systrace

- Systrace Basics - Why 60 fps?

- Android Systrace Basics - SystemServer Explained

- Systrace Basics - SurfaceFlinger Explained

- Systrace Basics - Input Explained

- Systrace Basics - Vsync Explained

- Systrace Basics - Vsync-App: Detailed Explanation of Choreographer-Based Rendering Mechanism

- Systrace Basics - MainThread and RenderThread Explained

- Systrace Basics - Binder and Lock Contention Explained

- Systrace Basics - Triple Buffer Explained

- Systrace Basics - CPU Info Explained

- Systrace Smoothness in Action 1: Understanding Jank Principles

- Systrace Smoothness in Action 2: Case Analysis - MIUI Launcher Scroll Jank Analysis

- Systrace Smoothness in Action 3: FAQs During Jank Analysis

- Systrace Responsiveness in Action 1: Understanding Responsiveness Principles

- Systrace Responsiveness in Action 2: Responsiveness Analysis - Using App Startup as an Example

- Systrace Responsiveness in Action 3: Extended Knowledge on Responsiveness

- Systrace Thread CPU State Analysis Tips - Runnable

- Systrace Thread CPU State Analysis Tips - Running

- Systrace Thread CPU State Analysis Tips - Sleep and Uninterruptible Sleep

Main Content

Here is the official definition of SurfaceFlinger:

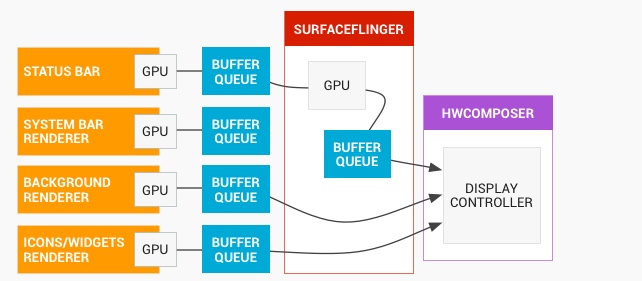

- Most apps display three layers on the screen: a status bar at the top, a navigation bar at the bottom or side, and the app interface itself. Some apps may have more or fewer layers (e.g., the default home screen app has a dedicated wallpaper layer, while a fullscreen game might hide the status bar). Each layer can be updated independently. The status bar and navigation bar are rendered by system processes, while the app layer is rendered by the app, with no coordination between them.

- Device displays refresh at a fixed rate, typically 60 fps on phones and tablets. If content updates during a refresh, tearing occurs; therefore, it’s essential to update content only between cycles. The system receives a signal from the display device when it’s safe to update content. For historical reasons, we call this the VSYNC signal.

- Refresh rates may change over time; for example, some mobile devices range between 58 fps and 62 fps depending on current conditions. For HDMI-connected TVs, the rate can theoretically drop to 24 Hz or 48 Hz to match video. Since each refresh cycle can only update the screen once, submitting buffers at 200 fps is wasteful as most frames will be discarded.

SurfaceFlingerdoesn’t act every time an app submits a buffer; instead, it wakes up only when the display device is ready for a new buffer. - When a VSYNC signal arrives,

SurfaceFlingertraverses its layer list searching for new buffers. If found, it acquires them; otherwise, it continues using previously acquired buffers.SurfaceFlingermust always display content, so it retains one buffer. If a layer lacks a submitted buffer, it is ignored. - After collecting all buffers for visible layers,

SurfaceFlingerconsults the Hardware Composer on how to perform composition.

— Cited from SurfaceFlinger and Hardware Composer

Below is the flowchart corresponding to this process. Simply put, SurfaceFlinger‘s primary function is: it accepts data buffers from multiple sources, composites them, and sends them to the display device.

In Systrace, we focus on the parts corresponding to this diagram:

- App Section

- BufferQueue Section

- SurfaceFlinger Section

- HWComposer Section

These four parts appear in Systrace in chronological order: 1, 2, 3, then 4. Let’s examine the rendering flow from these four perspectives.

App Section

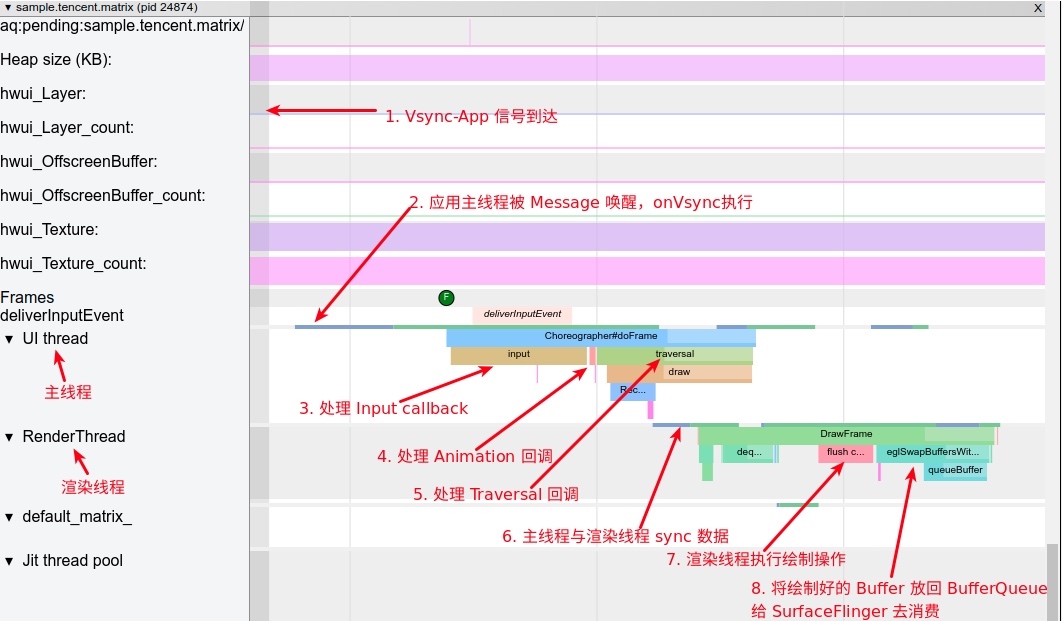

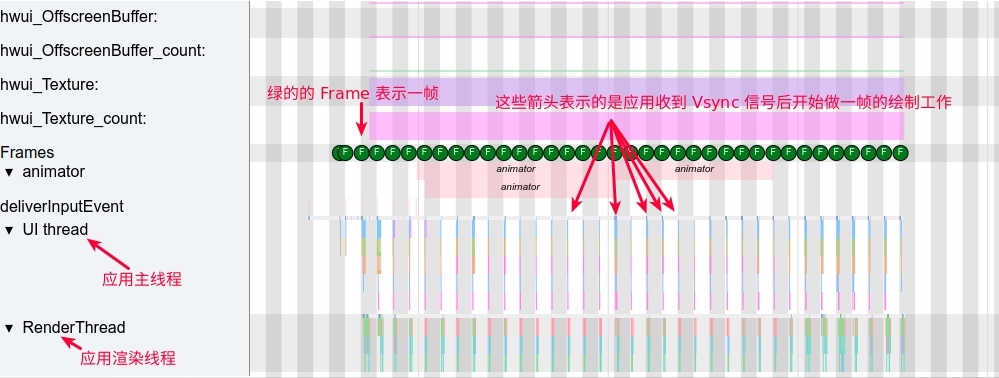

The App section is detailed in Systrace Basics - MainThread and RenderThread Explained. The primary flow is shown below:

From SurfaceFlinger‘s perspective, the App section is responsible for producing the Surfaces needed for composition.

The interaction between an App and SurfaceFlinger centers on three points:

- Vsync signal reception and processing.

RenderThread‘sdequeueBuffer.RenderThread‘squeueBuffer.

Vsync Signal Reception and Processing

This is covered in Android Based on Choreographer Rendering Mechanism Explained. The first item in the diagram marks the Vsync-App signal arriving from SurfaceFlinger. Upon receiving this, the app begins preparing its frame.

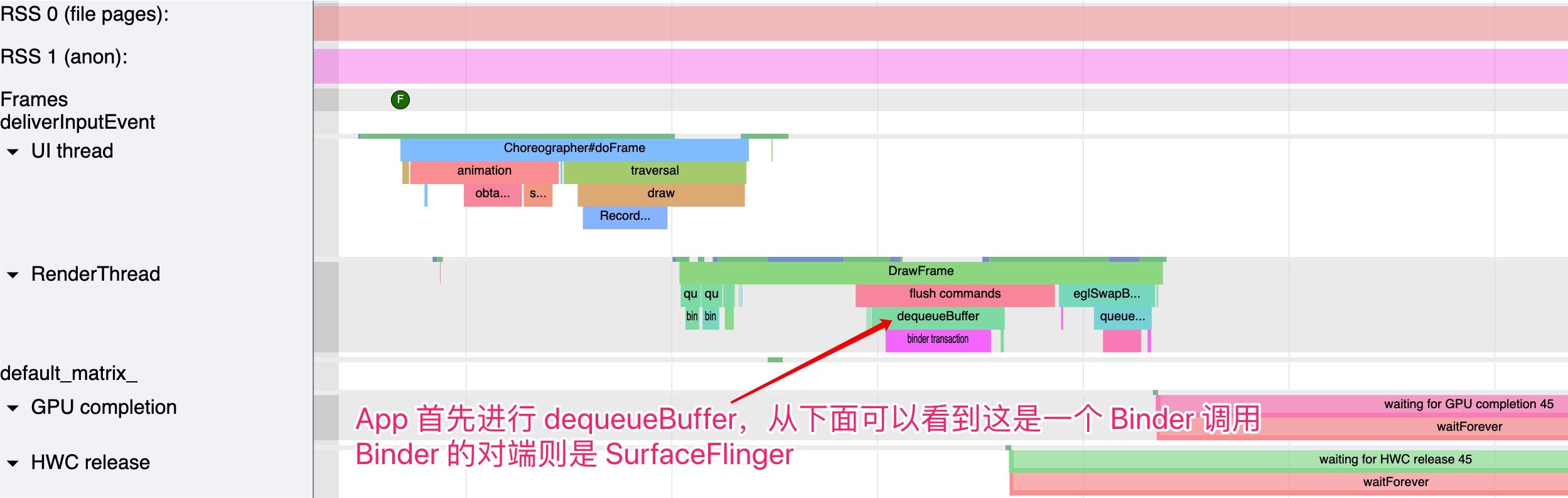

RenderThread’s dequeueBuffer

dequeueBuffer means requesting a buffer from the BufferQueue within SurfaceFlinger. Before rendering begins, the app makes a Binder call to obtain a buffer:

App-side Systrace:

SurfaceFlinger-side Systrace:

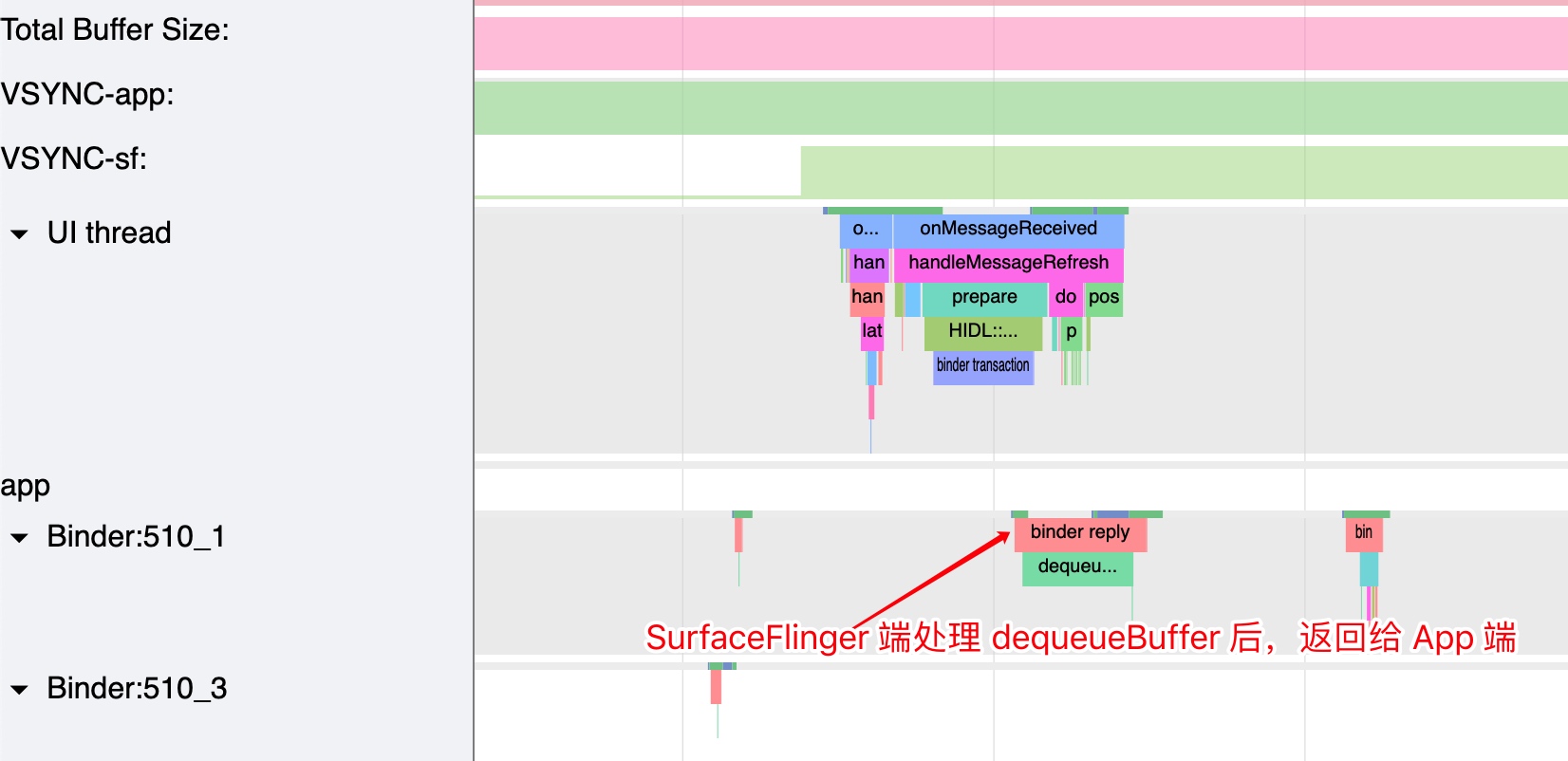

RenderThread’s queueBuffer

queueBuffer puts the buffer back into the BufferQueue after the app finishes processing (writing drawcalls). This follows the eglSwapBuffersWithDamageKHR -> queueBuffer flow:

App-side Systrace:

SurfaceFlinger-side Systrace:

Through these three parts, you should have a clear understanding of the flow depicted below:

BufferQueue Section

BufferQueue is discussed in Systrace Basics - Triple Buffer Explained. Each process with a display interface has a corresponding BufferQueue. The consumer creates and owns the data structure, which can exist in a different process from the producer. The flow is:

In this example, the App is the producer (filling buffers), and SurfaceFlinger is the consumer (compositing buffers).

- dequeue (initiated by producer): When the producer needs a buffer, it calls

dequeueBuffer(), specifying width, height, pixel format, and flags. - queue (initiated by producer): After filling the buffer, the producer calls

queueBuffer()to return it to the queue. - acquire (initiated by consumer): The consumer calls

acquireBuffer()to take the buffer and use its content. - release (initiated by consumer): Once finished, the consumer calls

releaseBuffer()to return the buffer to the queue.

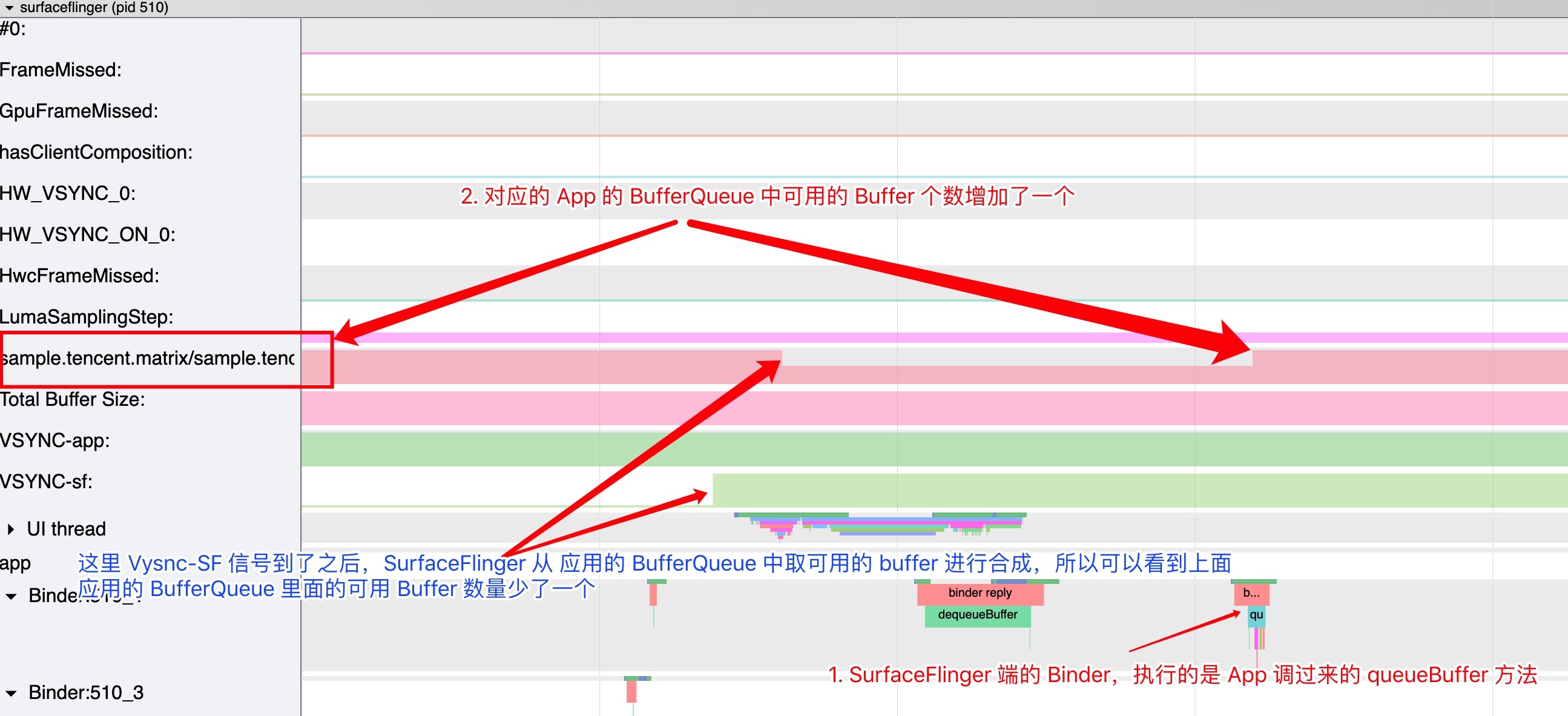

SurfaceFlinger Section

Workflow

As mentioned, SurfaceFlinger‘s main job is composition:

When a VSYNC signal arrives,

SurfaceFlingertraverses its layer list searching for new buffers. If found, it acquires them; otherwise, it continues using previously acquired buffers… It then asks the Hardware Composer how to perform composition.

In Systrace, the main thread starts working upon receiving the Vsync signal:

The corresponding code handles two main messages:

MessageQueue::INVALIDATE— executeshandleMessageTransactionandhandleMessageInvalidate.MessageQueue::REFRESH— executeshandleMessageRefresh.

frameworks/native/services/surfaceflinger/SurfaceFlinger.cpp

1 | void SurfaceFlinger::onMessageReceived(int32_t what) NO_THREAD_SAFETY_ANALYSIS { |

Major functional categories in handleMessageRefresh:

- Preparation

preComposition()rebuildLayerStacks()calculateWorkingSet()

- Composition

beginFrame(display)prepareFrame(display)doDebugFlashRegions(display, repaintEverything)doComposition(display, repaintEverything)

- Cleanup

logLayerStats()postFrame()postComposition()

Given the display system’s complexity, we won’t cover every detail. If your work involves this area, familiarize yourself with all flows; otherwise, understanding the high-level logic is enough.

Dropped Frames (Jank)

To determine if an app is dropping frames in Systrace, look at SurfaceFlinger:

- Does the

SurfaceFlingermain thread skip composition at eachVsync-SF? - If it skips, find the reason:

- No available buffers?

- Occuppied by other tasks (screenshot, HWC, etc.)?

- Waiting for

presentFence? - Waiting for GPU fence?

- If composition occurs, check if your app’s available buffer count is normal. If it’s 0, investigate why the app didn’t

queueBufferin time (likely an app-side issue), as the composition might have been triggered by other processes having available buffers.

For more details on reading this in Systrace, see Systrace Basics - Triple Buffer Explained - Jank Detection.

HWComposer Section

Refer to the official introduction for Hardware Composer HAL (HWC):

- HWC determines the most efficient way to composite buffers using available hardware. As a HAL, its implementation is device-specific and typically provided by the display hardware OEM.

- Overlay planes composite multiple buffers in hardware rather than the GPU. For example, a portrait phone screen with a status bar, navigation bar, and app content can use:

- Render app content to a temporary buffer, then render the status and navigation bars on top, then send that buffer to display hardware.

- Send all three buffers to display hardware and instruct it to read different screen parts from different buffers. This is significantly more efficient.

- Display processor capabilities vary. HWC performs these calculations to achieve optimal performance:

SurfaceFlingerprovides a layer list and asks, “How do you want to handle these?”- HWC marks each layer as either an overlay or GLES composition.

SurfaceFlingerhandles GLES composition, sends the output buffer to HWC, and lets HWC handle the rest.

- When screen content doesn’t change, overlays can be less efficient than GL composition, especially with transparent pixels. HWC may opt for GLES composition in such cases to save battery during idle.

- Android 4.4+ devices typically support 4 overlay planes. Exceeding this triggers GLES composition for some layers, significantly affecting energy and performance.

— Cited from SurfaceFlinger and Hardware Composer

Continuing with the SurfaceFlinger main thread, here is the communication with HWC (step 3 above):

This corresponds to the latter part of the earlier diagram:

Details are extensive. HWC’s performance critical; issues like insufficient performance or slow interrupts can cause jank, as noted in Overview of Jank Causes in Android - System Side.

For more HWC knowledge, see Android P Display System (1): Hardware Composition HWC2 and the related series.

References

- Android P Display System (1): Hardware Composition HWC2

- Android P Graphics Display System

- Definition of SurfaceFlinger

- SurfaceFlinger Analysis Document

About Me && Blog

Below is my personal intro and related links. I look forward to exchanging ideas with fellow professionals. “When three walk together, one can always be my teacher!”

- Blogger Intro: Includes personal WeChat and WeChat group links.

- Blog Content Navigation: A guide for my blog content.

- Curated Excellent Blog Articles - Android Performance Optimization Must-Knows: Welcome to recommend projects/articles.

- Android Performance Optimization Knowledge Planet: Welcome to join and thank you for your support~

One walks faster alone, but a group walks further together.