Preface

This article serves as a set of learning notes documenting the basic workflow of RenderThread in hwui as introduced in Android 5.0. Since these are notes, some details might not be exhaustive. Instead, I aim to walk through the general flow and highlight the key stages of its operation for future reference when debugging.

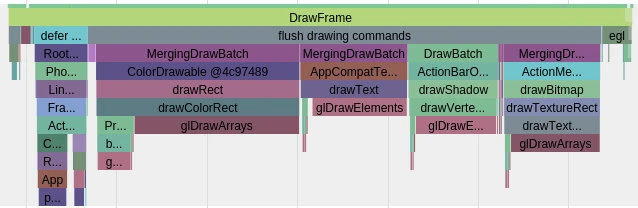

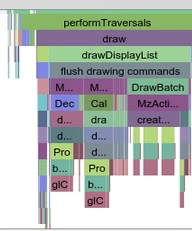

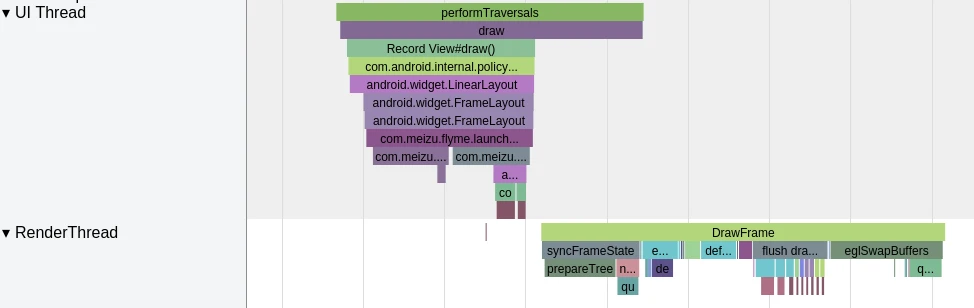

The image below shows a Systrace capture of the first Draw operation by the RenderThread during an application startup. We can trace the RenderThread workflow by observing the sequence of events in this trace. If you are familiar with the application startup process, you know that the entire interface is only displayed on the phone after the first drawFrame is completed. Before this, the user sees the application’s StartingWindow.

Starting from the Java Layer

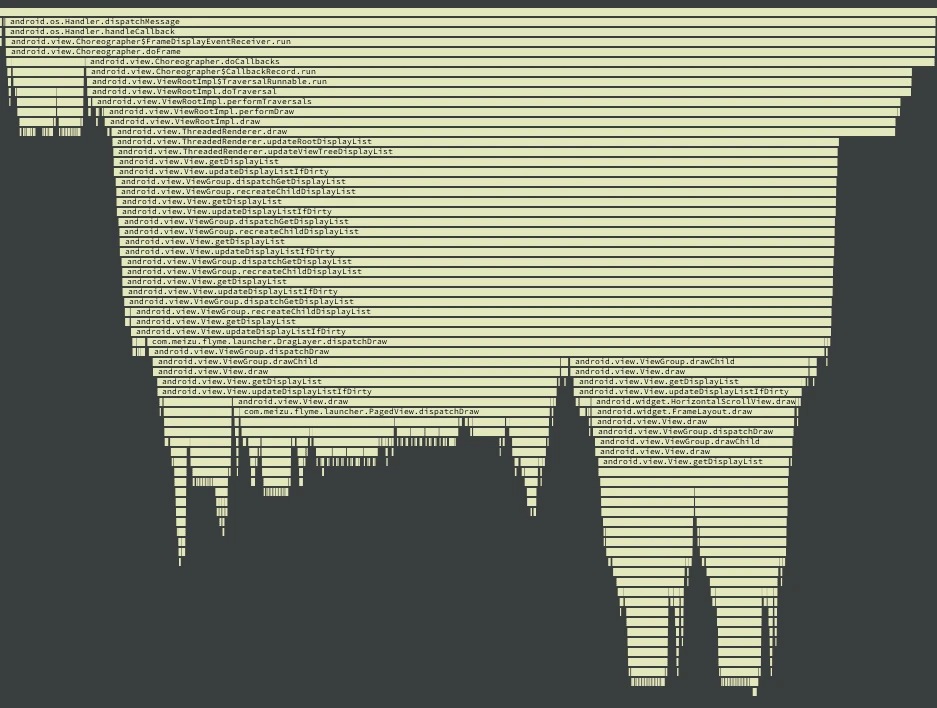

Every frame of an application begins its calculation and rendering upon receiving a VSYNC signal. This process originates from the Choreographer class. However, for the sake of brevity, let’s look directly at the call chain involved in rendering a single frame:

The drawFrame method in Choreographer calls the performTraversals method in ViewRootImpl, which eventually leads to performDraw(). This then calls draw(boolean fullRedrawNeeded), a private method in ViewRootImpl (distinct from the standard draw method we usually override).

1 | if (mAttachInfo.mHardwareRenderer != null && mAttachInfo.mHardwareRenderer.isEnabled()) { |

If the hardware rendering path is taken, mHardwareRenderer.draw is called. Here, mHardwareRenderer refers to ThreadedRenderer, whose draw function is as follows:

1 |

|

In this function, updateRootDisplayList(view, callbacks) performs the getDisplayList operation. This is followed by a crucial step:

1 | int syncResult = nSyncAndDrawFrame(mNativeProxy, frameTimeNanos, |

As we can see, this is a blocking operation. The Java layer waits for the Native layer to complete and return a result before proceeding.

The Native Layer

The Native code is located in android_view_ThreadedRenderer.cpp. The implementation is as follows:

1 | static int android_view_ThreadedRenderer_syncAndDrawFrame(JNIEnv* env, jobject clazz, |

The RenderProxy implementation can be found in frameworks/base/libs/hwui/renderthread/RenderProxy.cpp:

1 | int RenderProxy::syncAndDrawFrame(nsecs_t frameTimeNanos, nsecs_t recordDurationNanos, |

Here, mDrawFrameTask is a DrawFrameTask object, located in frameworks/base/libs/hwui/renderthread/DrawFrameTask.cpp. Its drawFrame code is:

1 | int DrawFrameTask::drawFrame(nsecs_t frameTimeNanos, nsecs_t recordDurationNanos) { |

The implementation of postAndWait() is:

1 | void DrawFrameTask::postAndWait() { |

This places the DrawFrameTask into the mRenderThread. The queue method in RenderThread is implemented as:

1 | void RenderThread::queue(RenderTask* task) { |

mQueue is a TaskQueue object, and its queue method is:

1 | void TaskQueue::queue(RenderTask* task) { |

Going back to the queue method in RenderThread, the wake() function is called:

1 | void Looper::wake() { |

The wake function is straightforward: it simply writes a single character “W” to the write end of a pipe. This wakes up the read end of the pipe, which was waiting for data.

HWUI RenderThread

Where do we go next? First, let’s get familiar with RenderThread. It inherits from Thread (defined in utils/Thread.h). Here is the RenderThread constructor:

1 | RenderThread::RenderThread() : Thread(true), Singleton<RenderThread>() |

The run method is documented in Thread:

1 | // Start the thread in threadLoop() which needs to be implemented. |

This triggers the threadLoop function, which is critical:

1 | bool RenderThread::threadLoop() { |

The for loop is an infinite loop. The pollOnce function blocks until mLooper->wake() is called. Once awakened, it proceeds to the while loop:

1 | while (RenderTask* task = nextTask(&nextWakeup)) { |

It retrieves the RenderTask from the queue and executes its run method. Based on our earlier tracing, we know this RenderTask is a DrawFrameTask. Its run method is as follows:

1 | void DrawFrameTask::run() { |

RenderThread.DrawFrame

The run method of DrawFrameTask coordinates the stages shown in the initial trace diagram. Let’s break down the DrawFrame process step by step, combining the code with the trace visualization.

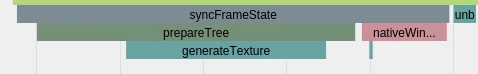

1. syncFrameState

The first major function is syncFrameState. As its name implies, it synchronizes architectural frame information, moving data maintained by the Java layer into the RenderThread.

Both the Main Thread and the Render Thread maintain their own set of application window view information. This separation allows them to operate without interfering with each other, maximizing parallelism. The Render Thread’s view information is synchronized from the Main Thread. Therefore, whenever the Main Thread’s view information changes, it must be synced to the Render Thread.

In the code, you’ll find two RenderNode types: one in hwui and one in View. Synchronization essentially involves copying data from the Java-side RenderNode to the hwui RenderNode. Note that the return value of syncFrameState is assigned to canUnblockUiThread. This boolean determines whether to wake the Main Thread early. If true, the Main Thread can resume work on other tasks immediately, rather than waiting for the entire draw operation to finish in the RenderThread. This is one of the most significant differences between Android 5.0 and Android 4.x.

1 | bool DrawFrameTask::syncFrameState(TreeInfo& info) { |

First is makeCurrent. Here, mContext is a CanvasContext object:

1 | void CanvasContext::makeCurrent() { |

mEglManager is an EglManager object:

1 | bool EglManager::makeCurrent(EGLSurface surface) { |

This logic checks if mCurrentSurface == surface. If they match, no re-initialization is needed. If it’s a different surface, eglMakeCurrent is called to recreate the context.

After makeCurrent, mContext->prepareTree(info) is called:

1 | void CanvasContext::prepareTree(TreeInfo& info) { |

Within this, mRootRenderNode->prepareTree(info) is the most important part. Back at the Java layer, the ThreadedRenderer initializes a pointer:

1 | long rootNodePtr = nCreateRootRenderNode(); |

This RootRenderNode is the root node of the view tree:

1 | mRootNode = RenderNode.adopt(rootNodePtr); |

Then a mNativeProxy pointer is created, initializing a RenderProxy object in the Native layer and passing rootNodePtr to it. CanvasContext is also initialized inside RenderProxy, receiving the same rootNodePtr.

We mentioned that the draw method in ThreadedRenderer first calls updateRootDisplayList (our familiar getDisplayList). This involves two steps: updateViewTreeDisplayList and then adding the root node to the DrawOp:

1 | canvas.insertReorderBarrier(); |

The final implementation is:

1 | status_t DisplayListRenderer::drawRenderNode(RenderNode* renderNode, Rect& dirty, int32_t flags) { |

Returning to CanvasContext::prepareTree, the mRootRenderNode is the one passed during initialization. Its implementation is in RenderNode.cpp:

1 | void RenderNode::prepareTree(TreeInfo& info) { |

Further details on these operations can be explored in the source code.

2. draw

After syncFrameState comes the draw operation:

1 | if (CC_LIKELY(canDrawThisFrame)) { |

The draw function in CanvasContext is a core method located in frameworks/base/libs/hwui/renderthread/CanvasContext.cpp (Wait, the original text says OpenGLRenderer.cpp, but in 5.0 it’s often in CanvasContext.cpp for ThreadedRenderer). Let’s follow the provided snippet:

1 | void CanvasContext::draw() { |

2.1 EglManager::beginFrame

While not shown in the immediate snippet above, beginFrame is typically called during this phase:

1 | void EglManager::beginFrame(EGLSurface surface, EGLint* width, EGLint* height) { |

makeCurrent manages the context, and eglBeginFrame validates parameter integrity.

2.2 prepareDirty

1 | status_t status; |

Here, mCanvas is an OpenGLRenderer object. Its prepareDirty implementation is:

1 | status_t OpenGLRenderer::prepareDirty(float left, float top, |

2.3 drawRenderNode

1 | Rect outBounds; |

Next, OpenGLRenderer::drawRenderNode is called to perform the actual rendering:

1 | status_t OpenGLRenderer::drawRenderNode(RenderNode* renderNode, Rect& dirty, int32_t replayFlags) { |

Here, renderNode is the RootRenderNode. Although this is just the beginning of the draw process, the key steps are already highlighted:

1 | renderNode->defer(deferStruct, 0); // Reordering |

These are the true core of the rendering engine. The implementation details are complex. For a deeper dive, I highly recommend Luo Shengyang’s article: Analysis of the Display List Rendering Process in Android UI Hardware Acceleration.

2.4 swapBuffers

1 | if (status & DrawGlInfo::kStatusDrew) { |

This ultimately calls the EGL function eglSwapBuffers(mEglDisplay, surface).

2.5 FinishFrame

1 | profiler().finishFrame(); |

Mainly used for recording timing information.

Summary

Since I’m a bit lazy and my summarizing skills don’t quite match Luo’s, I’ll quote his summary here. The overall RenderThread flow is as follows:

- Synchronize the Display List maintained by the Main Thread to the one maintained by the Render Thread. This synchronization is performed by the Render Thread while the Main Thread is blocked.

- If the synchronization completes successfully, the Main Thread is awakened. From this point, the Main Thread and Render Thread operate independently on their respective Display Lists. Otherwise, the Main Thread remains blocked until the Render Thread finishes rendering the current frame.

- Before rendering the Root Render Node’s Display List, the Render Thread first renders child nodes with Layers onto their own FBOs. Finally, it renders these FBOs alongside nodes without Layers onto the Frame Buffer (the graphics buffer requested from SurfaceFlinger). This buffer is then submitted to SurfaceFlinger for composition and display.

Step 2 is crucial because it allows the Main Thread and Render Thread to run in parallel. This means that while the Render Thread is rendering the current frame, the Main Thread can start preparing the Display List for the next frame, leading to a much smoother UI.

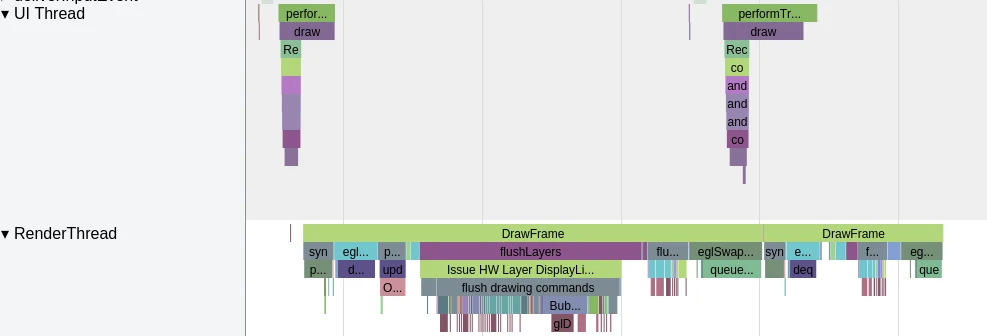

Before Android 5.0, without a RenderThread, everything happened on the Main Thread. This meant that the next frame could only be prepared after the current draw was complete, as shown below:

With Android 5.0, there are two scenarios:

In the second scenario, the RenderThread hasn’t finished drawing, but since it awakened the Main Thread early, the Main Thread can respond to the next Vsync signal on time and begin preparing the next frame. Even if the first frame took longer than usual (causing a dropped frame), the second frame remains unaffected.

About Me && Blog

Below are my personal details and links. I look forward to connecting and sharing knowledge with fellow developers!

- About Me: Includes my WeChat and WeChat group links.

- Blog Navigation: A guide to the content on this blog.

- Curated Android Performance Articles: A collection of must-read performance optimization articles. Self-nominations/recommendations are welcome!

- Android Performance Knowledge Planet: Join our community for more insights.

“If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.”